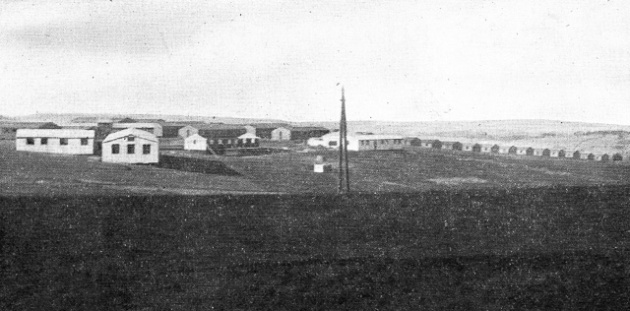

Hilder’s Military Hospital, Haslemere, England, photographed in 1915.

Postcard by Francis Frith.

Dear Pat

This is the hospital I am in [at] present. I am still in bed Nov 11th 1918. But getting on alright.

Jock

It was Armistice Day and John (a.k.a. Jock) Eastwood of ‘A’ Company, 3rd Battalion New Zealand Rifle Brigade had survived the Great War. Damaged but still alive.

Jock didn’t fit the popular modern image of a WWI soldier – a naive 20-something who thought it would be an adventure and all over by Christmas. It was 1917 when he pulled on the uniform by which time all such romantic notions had disappeared, along with the supply of 20-somethings to recruit or conscript. Armies involved in the conflict had been forced to raise their age limits. Jock was a 37 year-old self-employed “merchant” when he was called up.

Described as having fair hair, blue eyes and standing 5 ft 7 inches tall, he was a bachelor who lived with his unmarried sister (two years his senior) in Collingwood Street, Ponsonby, Auckland. She was not his “dependent” so may have been a partner in the business. Her given name was Martha but Jock always greeted her as Pat.

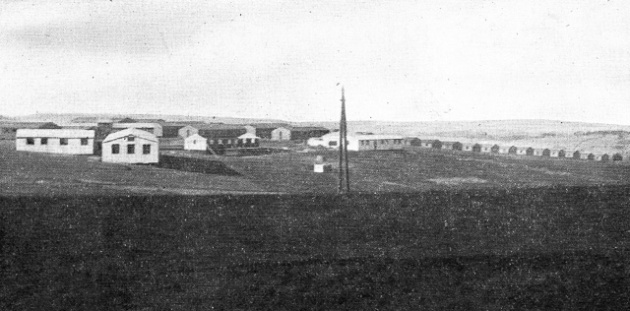

In an undated postcard of Featherston Camp he wrote, We were marched to Featherston on Saturday for shower bath. We have had no leave yet.

At the time of writing it is blowing like the devil. The place is the last created. The food is very good. We expect to leave here in 2 weeks.

Jock had been passed “fit for service” on 8th June with no problems except for his teeth. Their condition was stamped “For Treatment”, a fairly common ammendment to army medical forms at the time.

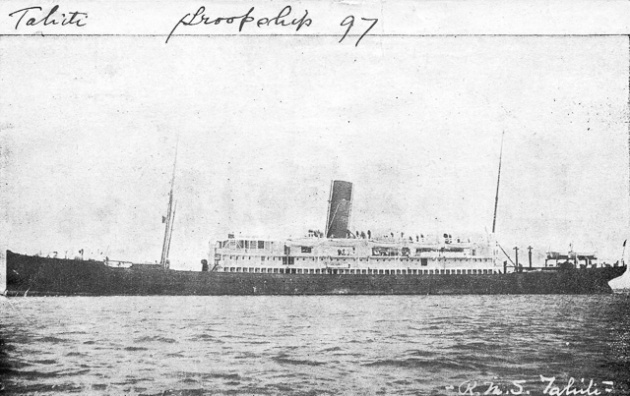

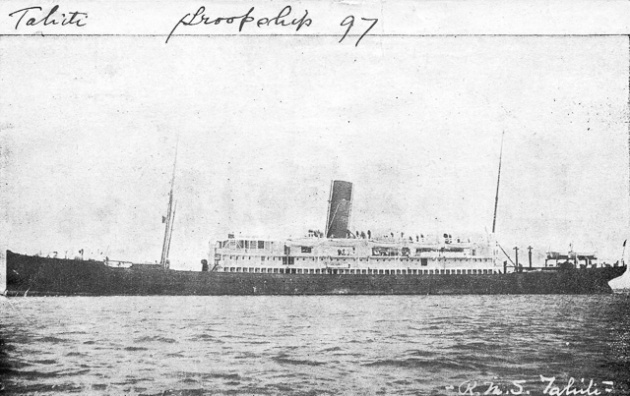

With military training behind him and, evidently, minus several teeth, he boarded the troopship Tahiti on 16th November 1917 and left Wellington as part of convoy 97 next day.

Alls well

Having good trip. Have not been sea sick. Getting teeth when we land.

The voyage lasted seven weeks and Tahiti disembarked her passengers at Liverpool on 7th January 1918. They went straight to Brocton Camp in Staffordshire, which was no great improvement on Featherston if these postcard images are any indication.

Jock wasted no time sending this card to his sister, posting it on the day he arrived.

Both cards look like they were produced quickly and cheaply. No message on either, just his name, army number – 62527 – and new address.

This would be luxury accommodation compared to what lay ahead. Jock was sent to France in late March, “attached Strength” at Abeele, and assigned to ‘A’ Company on 5th April. Ten months after signing up, he had finally arrived at the front.

Six months later, on 8th October, Rifleman John Eastwood suffered a gunshot wound to the head and was evacuated to the 83rd military base hospital at Boulogne where he was put on the danger list for over a fortnight. When judged well enough to travel, he was transfered to Cambridge Military Hospital at Aldershot in England. Hilder’s isn’t mentioned in his army record but it was an auxiliary hospital under the control of Cambridge and we know from Jock’s own hand that he was there when peace broke out.

Hilder’s had been a private house before the war, the residence of Lady Aberconway who donated it for the benefit of war casualties. She converted her London home to a hospital as well. Ironically, given the Ottoman Empire was on the enemy side, that building now houses the Turkish Embassy.

Jock was moved once more, to Walton-on-Thames in December, before being sent home on the ship Maheno in March 1919. His official discharge papers didn’t arrive until August, bearing the standard rubber stamp “No longer physically fit for war service on account of wounds received in action”. It seems like a heartless way to end the relationship. A simple “thank you” or “we appreciate your sacrifice” would not have gone amiss, but in 1919 Rifleman Eastwood was seen as just another British subject who had done his duty for the Empire.

Jock and Pat tried to return to normal life, now in a different house a couple of blocks away from Collingwood Street, at 34 Franklin Road. It was not to be. Pat died there on 27th December 1921, aged 44.

Jock died at Auckland Hospital on 7th July 1941 “in his 62nd year” leaving two brothers, a niece and two nephews to mourn his loss.

John/Jock Eastwood, and others like him, is unlikely to feature in history books. He was one of the faceless thousands given a number and a rifle and shipped off to a battlefield on the other side of the world, to endure conditions most of us can’t even imagine. A middle-aged man literally minding his own business who was plunged into a nightmare.

Jock was one of the lucky ones who managed to cheat death, but should be no less remembered for that on Armistice Day.

Text © Mike Warman.

Sources: NZ Army records, 5 postcards in my collection, Auckland Star and New Zealand Herald of various dates.

Note: Jock was a stranger to punctuation, and capital letters popped up at random. I have edited his words to make them easier to follow.

“Man has only a certain capacity for feeling, and that has been strained almost to breaking point by human needs. But now that the wants of our wounded are being seen to with hundreds of motor ambulances and hospitals fully equiped, now that the situation is more in hand, we can surely turn a little to the companions of man. They, poor things, have no option in this business; they had no responsibility, however remote and indirect, for its inception; get no benefit out of it of any kind whatever; know none of the sustaining sentiments of heroism; feel no satisfaction in duty done. They do not even – as the prayer for them untruly says – ‘offer their guileless lives for the wellbeing of their countries.’ They know nothing of countries; they do not offer themselves. Nothing so little pitiable as that. They are pressed into this service, which cuts them down before their time.”

“Man has only a certain capacity for feeling, and that has been strained almost to breaking point by human needs. But now that the wants of our wounded are being seen to with hundreds of motor ambulances and hospitals fully equiped, now that the situation is more in hand, we can surely turn a little to the companions of man. They, poor things, have no option in this business; they had no responsibility, however remote and indirect, for its inception; get no benefit out of it of any kind whatever; know none of the sustaining sentiments of heroism; feel no satisfaction in duty done. They do not even – as the prayer for them untruly says – ‘offer their guileless lives for the wellbeing of their countries.’ They know nothing of countries; they do not offer themselves. Nothing so little pitiable as that. They are pressed into this service, which cuts them down before their time.”

“The twin-screw steamer “Arabic,” 16,786 tons, is engaged in the White Star Line service from Mediterranean ports to Boston and New York, and is the largest liner regularly plying in this trade. This ship is noted for her graceful lines. She is 590 feet in length, and has a breadth of 69 feet. The “Arabic” public rooms are features of architectural splendour and luxurious furnishings. She has a verandah cafe and a photographic darkroom, which latter is of special service to camera lovers cruising the Mediterranean.”

“The twin-screw steamer “Arabic,” 16,786 tons, is engaged in the White Star Line service from Mediterranean ports to Boston and New York, and is the largest liner regularly plying in this trade. This ship is noted for her graceful lines. She is 590 feet in length, and has a breadth of 69 feet. The “Arabic” public rooms are features of architectural splendour and luxurious furnishings. She has a verandah cafe and a photographic darkroom, which latter is of special service to camera lovers cruising the Mediterranean.”